At the age of twelve, Easurk Emsen Charr emigrated to the United States in 1904, where he worked in the plantation fields of Hawai‘i. Despite his service in the US Army during World War I, he was denied citizenship. His wife, Evelyn Kim–an exchange student who emigrated in 1926–, was threatened with deportation several times. Thus began their more than 30-year struggle for naturalization. A resident of Portland, Mr. Charr later worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and in 1961 published an autobiography about his experience entitled, “The Golden Mountain.”

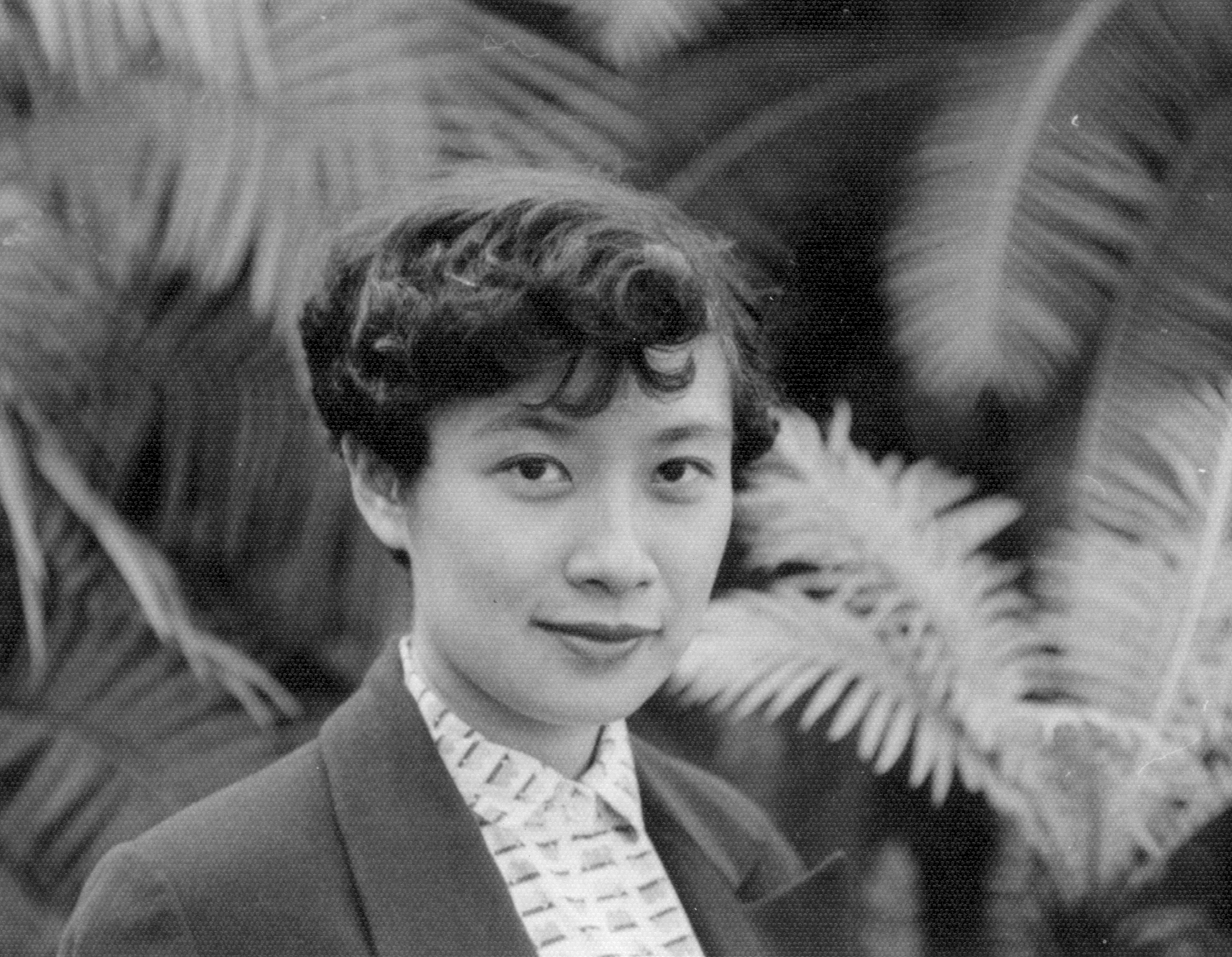

Their story now continues as their daughter, Anna Charr Kim, shares the story of her life and family in volume 5 of Korean American Historical Society’s Occasional Papers. Here, she adds to her father’s story by bringing her perspective to her parents’ experiences, thereby also articulating the life story of her mother. Dr. Kim’s perspective–that of a second-generation Korean American who grew up during the 1930s and 40s–is one that will become increasingly scarce in the years ahead.

“I am very pleased what we were able to feature Anna Charr Kim’s memoirs,” said Ick-Whan Lee, president and publisher. “Following an article published in KoreAM Journal a few years ago, she contacted us, and has been helping by collecting other oral histories from people of her generation for us ever since,” he continued.

Also included in volume 5 is the latest in a series of oral histories of Koreans who immigrated to Germany in the 1970s. The series, which began with a miner in volume 3, ends with a female nurse.

Essays on Korean American identity and heritage are another recurring feature of Occasional Papers. The authors of this volume’s collection lyrically reflect on the use of Korean heritage, persuasively complicate our definition of Korean American feminism, and strategically situate Korean American identity formation as part of the larger American political culture.

KAHS’ Community Reports presents the results of two studies on Korean American youths conducted by prominent scholars of Korean American sociology and social work (Kwang Chung Kim, Young In Song and Ailee Moon, and Eunai Shrake). Both reports suggest a shift from a Korean identity that is monolithic to one that is more pluralistic. Dr. Shrake’s study also reveals the need for culturally sensitive approaches to understanding parenting styles in addressing adolescent problem behavior.

These are followed by sports historian Joseph Svinth’s sequel to his volume 4 article on Korean boxers during the 1920s and 30s. “Fighting Spirit II” follows the careers of Walter Cho, Richard Shin and Kim Messer. With rare photographs, their experiences help us to re-examine and reinterpret the contributions of Korean Americans to American sport and entertainment during the first half of the 20th century.

Finally, Occasional Papers includes book reviews that offer evidence to the growing literature on the Korean American experience and diaspora. While all three reviews point to the expanding literature on Korean and Korean American studies, the reader will be reminded of how much more the field of Korean and Korean American studies can grow in the future.

Volume 5 of Occasional Papers will be available during the third national conference of the Korean American, Adoptee, Adoptive Family Network (KAAN) at the SeaTac Double Tree Hotel, July 27-29.